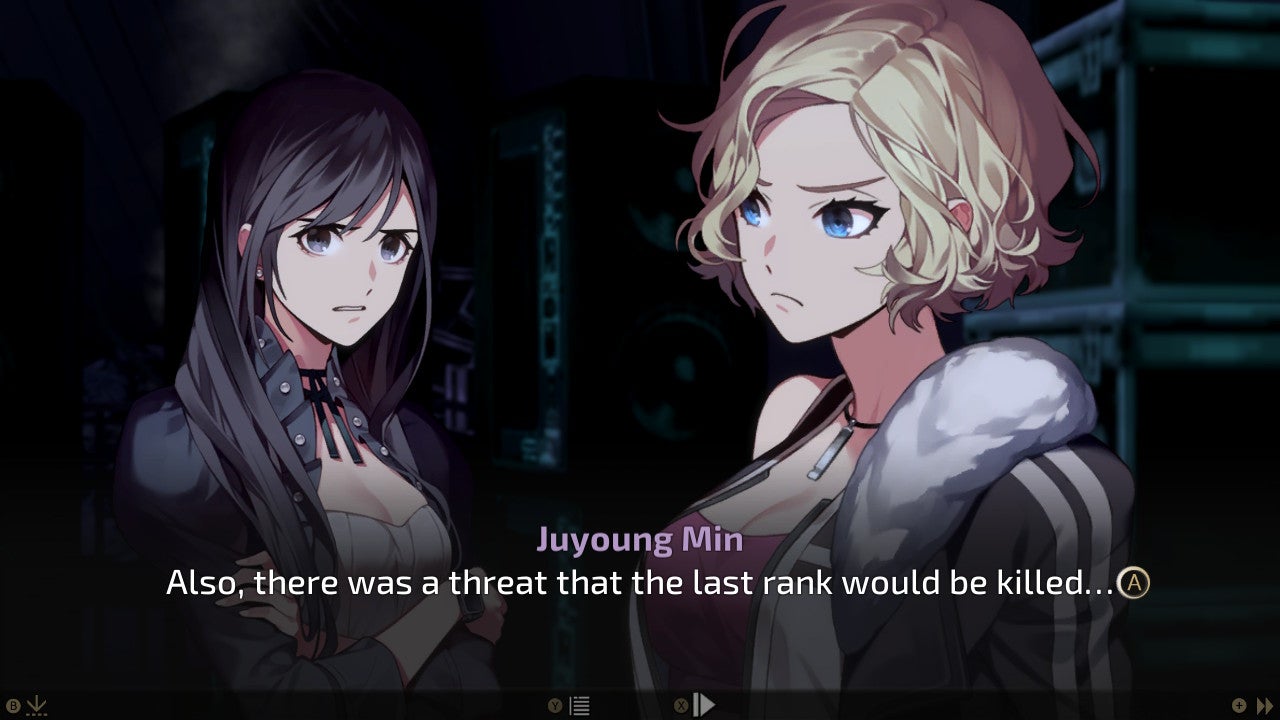

This year I saved a sleepy village from a monster, I tried to unite a divided caste society, and I started a band. I defended the innocent in court, tried to stay alive in a death game, fought with street gangs in a cyberpunk society and found the impostor among us. The twist is this - I did all of this in visual novels. Even if you get past the misconception of all visual novels being the weirdly horny games you sometimes come across on Steam’s Popular Up and Coming lists, visual novels can be difficult to talk about. I’m not saying the people who shy away from visual novels don’t like to read in general. But there is the expectation of interactivity with games, and to many, visual novels aren’t interactive enough - not even games like Ace Attorney, which according to the original definition of a visual novel, is technically an adventure game. Visual novels can encompass all genres - the wide range of experiences I’ve had this year alone also attest to how many stories fit a choice-driven format. Visual novels are a great way of studying branching decision-making in games and work particularly well with anything that asks players for a hard choice. Two games exemplified both the sheer narrative and technical work that goes into crafting unforeseen consequences. Gnosia, which came out in the West on Switch this year and is to receive a PC port, is a game where a group of people try to find out via discussion if one or more people in their midst (I say people, one of them is a dolphin in a spacesuit) is out to murder them. Because you’re talking to a bunch of computer-controlled people, this is a bit of a hard sell narratively, but the different roles you can inhabit and number of questions you can ask leads to so many different outcomes I would pay developer Petit Depotto good money to take a peek at their branching cause and effect models. Buried Stars, a Korean visual novel, is the better choice if you’re looking for a death game with a stronger narrative focus - I haven’t really played anything that compares to it since the golden age of Danganronpa/Zero Escape a good decade ago. It suffers from sub-par English translation, which unfortunately is a common problem, but it takes an interesting stab at social media culture and the hunt for fame. In it, a group of contestants of a pop idol show get trapped in a studio, only to find out that this, as well as their potential death at the hands of a stranger, is all part of the show. Many visual novels are dating games and it feels to me like there’s an increasing interest in such games among Western developers and players, judging by the reception of this year’s Boyfriend Dungeon, the game where you date a bunch of sexy sometimes-weapons. I don’t know if visual novels are a direct influence on the dating aspects in games like Dragon Age, but people like to choose characters to date, with the romance adding another facet to their interactive experience, just as romance is part of many stories in other media. Visual novels with dating as their main component, called otome games when the protagonist is a woman, are a lot more than Doki Doki Literature Club wants you to believe. Doki Doki, which got an enhanced re-release and console versions this year, was meant as a form of satire of the harem-like nature of visual novels where every character is immediately into the protagonist. In reality, these games are interesting precisely because that isn’t what happens. While there are ways to ensure you get to date your favourite, that decision either changes the plot fundamentally, or is even largely separate from the plot. Nowhere was that more apparent than in Nippon Cultural Broadcasting Co’s visual novel Bustafellows. Bustafellows puzzled a great many people this year when it emerged as the top reviewed game on Metacritic, and then surprised them even further by being much less about dating than about the dysfunctional nature of our legal systems. Its heroine Teuta is a young journalist trying to stop a murder by travelling back in time. The catch - she can only travel so far, and each time she travels, she ends up in a body that is not her own. The murder itself is the result of a group of admittedly beautiful young men playing vigilante to punish those criminals the law won’t pin down. This is a multi-faceted narrative about the meaning of crime and justice that you incidentally also get to date pretty anime boys in. Another of my favourites this year, the Switch-exclusive Olympia Soirée, showcases the lengths visual novels will go in terms of worldbuilding. Olympia, a girl taken from her home by force, must find a partner to ensure the continuation of her race. Race in this case is defined by primary colour - people from the blue caste have blue hair and blue eyes, and so forth, but there are primary colours and secondary colours, people with no colour, leading to an astoundingly complex system for what is, admittedly, a pretty standard “oh no, we need to do it to save humanity” trope. I usually shy away from games which for that very reason can be seen as misogynistic, but Olympia Soirée acknowledges the problems of its own setup, but it’s also an interesting thought experiment - can a game that’s fundamentally about dating guys criticise the pressure exerted on women to keep societies such as Japan from overaging? Visual novels may not have the answer, but they look to discuss topics many other games can’t or won’t make room for, not least because they have to focus on building their narratives around certain game mechanics. I would however make myself a hypocrite if I were to imply that there aren’t a lot of visual novels people simply enjoy for the romance, or the promise of explicit material. Even without explicit visuals, visual novels frequently earn 18+ ratings and content warnings. Many visual novel publishers have devised a route to make such content available without violating shop content policies - they will offer an all-ages (or at least considerably less explicit) version of a game on Steam and offer paid DLCs for the missing content on their own platforms. This is not the article to unpack how platforms deal with sexual content while having no such policies in place for games featuring considerable gun violence - rather, this practice throws up some interesting questions on on the opt-in nature of some content. These visual novels absolutely work without explicit content, but they were designed with it in mind. Is there a right way to treat such games, and can it be done without shying away from certain subjects? Western visual novel makers often aren’t waiting for the approval of business platforms and publishers, which leads to a fascinating culture of entirely Kickstarter-backed visual novels and independent efforts available via itch.io. Some of the best games I’ve played this year, such as the Steam release of fantasy dating sim When The Night Comes by Lunaris Games, are precision-designed for the communities excited to back them, and embrace that romance is just as much of a fun aspect of their games as the overarching adventure. Additionally, these games are a driving force of acceptance for different relationship models, and frankly, kinks. Nowhere else in games do I see topics like polyamory discussed openly, and the medium is richer for diverse representation of a wide breadth of topics. In many ways, visual novels are a video game subculture to Western players, but this year was an amazing example for their potential to appeal to many different players and game makers alike, and the subjects connected to their increasing success.