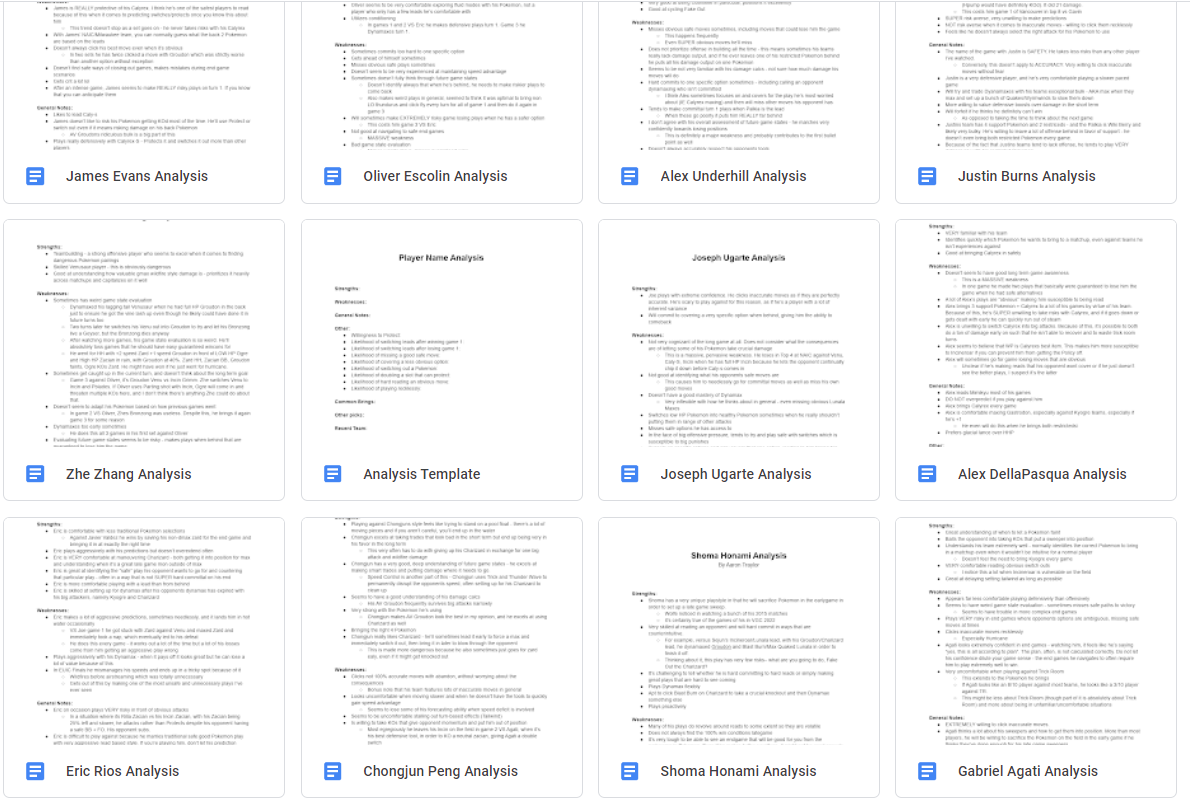

In addition to Nuzlocke rules, some particularly die-hard Pokémon fans like to use ‘hardcore’ versions, where you have to stick to certain level caps, like never going above the highest level Pokémon of the next Gym Leader, and where most items are banned, with only those held and triggered in-battle by your own Pokémon allowed. Beyond that: one further stage of excessive challenge. Some fans have created mods for older Pokémon games to increase their difficulty. Most notorious of all is Emerald Kaizo, a total reworking of that legendary 2004 game that turns every short-wearing, barely-out-of-preschool trainer into a competitive-tier opponent. Think top stats, higher levels, tournament-quality movesets and a totally reworked, systematic AI, tuned to maximum efficiency and aggression. Defeating Emerald Kaizo is a genuine achievement with a standard playthrough, requiring a working knowledge of how competitive Pokémon operates, from EVs and IVs (effort and individual values, respectively) to team building and in-game strategy. Defeating it with Nuzlocke rules, meanwhile, is extraordinarily hard, an often months-long grind for a select few players. Defeating Emerald Kaizo with these particular hardcore Nuzlocke rules had, at the time of this series, been done by exactly one player. Enter Wolfe Glick, 2016 World Champion and one of, if not the, best competitive Pokémon players in the world. In his own words. Glick had attempted exactly one standard Nuzlocke before, on the base version of Emerald, before jumping to the hardcore Kaizo version straight away. And while he’s been very well-known in competitive Pokémon circles for a while - he started competing over a decade ago, in 2011 - back in early 2021 the world of ‘content creation’ was relatively new to him still. You realise, as you follow the melodrama of his run, mourning fallen comrades and cursing recurring enemies, that you’re also watching a relatively young entertainer come into their prime. Alongside the knack he quickly finds for the challenge itself, you can see him honing a personal style. Affable, goofy, overtly intelligent. A little arrogant. But arrogant in the way the most popular sportspeople often quietly are, but are rarely begrudged for - because it’s only occasional that you see it, and because it’s earned. In the live streams, which last for hours before being cut down into new episodes of the run, you see more of his actual personality. He’s more scientific, more circumspect about conclusions, and has a habit of self-correcting, saying one thing and then taking it back to be replaced with something more precise. You also see the kind of wizardry that goes into beating this kind of challenge. By the end, he’s the third person in the world to have ever completed it. Second was another streamer known as Pokémon Challenges, or simply Jan, a friend of Glick’s and veritable expert of the subgenre, who’s spent over 4,000 hours playing Nuzlockes for a living, and who both devised these particular rules and gave Glick a few tips for a running start. Glick would be the first to admit he would’ve taken longer without the initial help, and yet: Jan of Pokémon Challenges took a hugely admirable (and appropriate) 151 attempts to beat this thing. Glick, having attempted just the one, standard Nuzlocke before, did it in less than half the time. To navigate it all he took those starting notes from Jan and the bespoke calculators assembled by the community, and constructed a monumentally detailed, battle-by-battle, Pokémon-by-Pokémon, move-by-move plan of what to do and when. Everything from which Pokémon needed to be caught and where (including an endless run of bad luck searching for a Lanturn with the right nature) and which opponents he’d need to keep which counters alive for was mapped out, his thinking often revealed as sudden bursts of detail, multiple paragraphs of theory for a single enemy Pokémon flashed quickly on screen. It is, you realise, typical for Glick. Talking to Glick, however, something else becomes clear. The Pokémon Company had cancelled all official, in-person events for two years through the height of the pandemic. It meant Wolfe Glick was trying to make the most of his time, to keep busy, make a go of YouTube while keeping his competitive mind sharp. Glick completing the hardest single-player challenge in Pokémon is like an elite footballer running half-marathons in the off season. Undoubtedly tough, if you’re the majority of people, but ultimately for him just a jog in the park. Glick’s real goal, as he often tells me - and often talks about in public - is far more ambitious: to master the art of competitive Pokémon, and become the undisputed greatest player of all time. His obstacle is the game itself. Wolfe Glick is determined to master a game that does not want to be mastered. The first time I speak with Wolfe Glick, it’s via Zoom. This first conversation feels as much a planning meeting as an interview, as though he’s scoping out a new project or challenge before him, sizing up a potential task. But behind a professional-sounding microphone, in front of a green screen, Glick is also perhaps at his most comfortable. Here, he’s as you see him on his live streams and in his earlier, unscripted videos. Talkative, immediately eager to explain the joys and the complexities of Pokémon - he would argue they’re one and the same - and immediately, obsessively animated when you give him the chance. “The reason that Pokémon is not more popular as a competitive game is not because the game itself has any issues,” Glick tells me mid-way into the conversation, at once revealing a problem I didn’t know existed and positing the solution he’s since found. “I mean, it has issues, but that’s not the reason. It’s because people don’t know about it, they don’t understand it, right? It’s an incredible game. “And as someone who is pretty much as deep into it as anyone so far, it is truly, like, a remarkable, beautiful thing. And people just don’t know it. And they don’t know how to find out about that. And so my goal is to break down those barriers and say, you know, ‘Hey! You. This thing is cool. You might like it. Let me pull back the curtain a little bit. Let me show you what’s going on here. Because I think it’s really cool. And I think that other people can think that too.’” Glick talks about this obligation often. It is arguably his ultimate quest. Or maybe one that sits alongside his other ultimate quest to be the best of all time - we talk about both in just the first hour. For Glick there’s an air of responsibility to all this, as though it’s only right that he take on the job that arguably the Pokémon Company - which barely funds competitive play and stays largely removed from it - should be taking on itself. For Glick it’s a void that he ought to fill, for no reason other than there’s simply nobody else who could do it better. “My goal is to make competitive Pokémon as big as it can be, and I think I have the tools to do that,” he says. “And so my content is geared towards that - I make content that’s really general right now. I’m not I’m not making content for hardcore, super intense, you know, ‘serious’ VGC players, because that’s like, a couple thousand people. My goal is to make content that anyone who knows about Pokémon can watch and enjoy, and then as they watch more content, eventually, they’ll be exposed to the VGC stuff, and then learn about it that way. That’s the goal.” The tools Glick’s talking about are in part his skills - Glick has a reputation for more inventive team compositions and surprise moves - and that natural charisma in front of a camera. But it’s also down to something arguably even rarer in competitive Pokémon. Glick, compared to any other competitor, benefits from an unparalleled longevity. Pokémon VGC players have a strangely short shelf-life, even by other esports’ notoriously fleeting standards, and it’s his ability to outlast the competition that Glick feels makes him one of, if not the best players to grace the game. He’s been playing competitive Pokémon since 2011, and many of his records - two wins at the US Nationals, a win at the US and Canada Internationals in 2019, a Players Cup, the most qualifications for Worlds, the most “top cuts” at Worlds (the final rounds of 24 players), six top-sixteen finishes, and his record as the only player to have won every level of tournament in the professional game - come directly from his ability to stick at it longer than the competition. By contrast, only one person, Ray Rizzo of the USA, has ever won the VGC Masters World Championship more than once, winning back-to-back finals in 2010, 2011, and 2012. But then the drop-off was sharp. In 2013 he was knocked out in the first round of Worlds, in 2015 he failed to qualify at all, and he’s since retired from professional play. Wolfe Glick is the only other to have appeared in two finals, including his 2016 win. He lost the other final to Rizzo in 2012. “I don’t think that Pokémon is a game you should be playing every single weekend,” Glick says, setting up to explain another solution to another as yet unexplained problem: This short shelf-life of Pokémon’s top players primarily comes from burnout. With such low financial incentives beyond travel awards to more tournaments - the prize for winning Worlds in 2022 was $10,000, scaling down to $1,500 for those in 9th-16th and nothing for any finishes below that - people who play Pokémon competitively “overwhelmingly do it because they like the game,” he says. Most competitive players, often in their late teens or early 20s, treat it as a hobby they can enjoy alongside things like university or early career jobs. The flipside to this: if a player starts to lose their passion for the game, there’s little outside incentive to keep at it. The risk of burnout to Glick is a risk to everything he’s tried to build so far, and managing that has become an active part of his preparation for major tournaments as anything else - but doing so comes with one crucial tradeoff. Qualifying for the World Championships, Pokémon’s singular, tentpole tournament, is much easier to do if you play the game more often. Worlds is built on an awkward qualification system. For those outside of Japan and South Korea, which have their tournaments run by a different organisation, getting to Worlds means earning a certain number of Championship Points, or CP. Competing in different sized tournaments earns you different amounts of points, according to your finish, but there are lots of caveats here - limits to how many times you can compete in tournaments of a certain kind and have your points count; how many competitors there are in the tournament itself, and so on. This combines with the structure of the Worlds tournament itself. The first day is the easiest to qualify for, requiring 400 points for players in Glick’s US and Canada Masters division, which can be earned by winning a single international tournament, or a combination of a few decent finishes. But by grinding out the games to earn even more points, some players can earn a bye to day two, by which point the field of competitors has already been thinned down dramatically. This year, in the US, you’ll have needed to finish in the top 12 points-earners in the region to earn a bye. In the simplest terms: competing in more tournaments increases your chances of earning enough points to qualify for Worlds; competing in even more tournaments helps your chance of winning it. “It’s a quantity over quality kind of thing,” Glick explains. There are some limits to how many tournaments you can attend to grind for points, but the limits are so high that, in his words, “almost nobody hits them.” The people who travel every single weekend - often flying across North America to do so - end up as the majority of those in the top point-earning spots. “You can qualify for the World Championships [by] never going to an event bigger than eight people.” All this means that for Glick to maintain that longevity, he’s had to set boundaries - even if it means a tougher run at the World Championships themselves. He goes by a rule where, if at least one friend of his isn’t attending a tournament, he just won’t go. “I don’t know if I’d be able to still enjoy the game if I didn’t have good friends also playing, to see at events and to work [with] on the tournaments. That’s a really big thing for me personally.” “Yes,” he says, “you can play all the time and you can qualify for Worlds by grinding and you can get there. If your goal is to get to Worlds, that’s fine. But for someone like me whose goal is to, like, be the best player of all time, playing more weekends isn’t gonna make me better - at a certain point it’s just gonna burn me out and make me not as good.” As our conversation progresses, Glick turns to the topic of Pokémon itself. He talks about it like a physicist might talk of some newly discovered, as yet unexplained natural law, speaking with a kind of infatuation with its untamed complexity, as if it were a phenomenon as much as a game. I ask him to explain why it’s so beautiful to me as if I were a layperson, which compared to him I very much am, and his answer hops between analogies, describing it first something that’s “always changing,” how “it’s like holding water in your hands,” or how thinking about this game strategically is “like looking at this gigantic painting, where you can look at one little bit and be like, ‘Oh this is what’s going on’, then ’this is what’s going on’ - but the whole thing is so complex, and there’s so much room for self-expression.” We talk of the changing meta - the prevailing strategy, that might be a certain move or certain Pokémon considered strong enough to be near ubiquitous - as though it were an ecosystem, where an abundance of, say, rabbits, might naturally lead to a rise in foxes, “but then what if you could introduce a totally new animal?” he posits, “What if you’re like, ‘Oh, because there’s so many foxes, I think this is a really good time for bald eagles?’” For those who’ve only played the single-player portion of Pokémon, battling through the Elite Four and collecting them all, this can all sound mighty strange. Pokémon is still a series aimed at seven-year-olds, after all. But where each new entry has been more approachable to the newer, younger players of today and, by dint of that, less challenging than the last, competitive Pokémon only gets more complex. In large part that’s down to scale. In official VGC matches, using Pokémon Sword and Shield for the final time this year, players play best-of-three rounds against each other in what’s called a Doubles format, where each player sends out two Pokémon at a time from their team of four - those four themselves chosen before each round, from a roster of six they locked in before the match. You can use almost any Pokémon that’s been released so far - there are a few restrictions, on only the most powerful handful of creatures - but that complexity goes far beyond the sheer number of Pokémon, which already sits at a whopping 905 before Pokémon Scarlet and Violet are released this year. Each of those Pokémon has its own combination of one or two out of 18 types, for instance. Plus one of several abilities, one of 25 natures, four of about 60 moves, and an “almost infinite” combination of their own base stats and the IVs (Individual Values they’re bred to have) and EVs (Effort Values they acquire from training) that a player can use to modify those stats within a certain range. Multiply all those factors together, and you get a number of combinations high enough to be considered impossible to prepare for. Naturally, a “meta” of prevailing strategies forms with each cycle of games, which narrows things down considerably on paper. But, as Glick explains again, with this year in particular even that has left the range of possibilities remarkably open. “The current format is very, very, very wide, in the sense that it’s really - decentralised is the wrong word, because it is somewhat centralised - but what I would say is: the best Pokémon right now are not so much better than the Pokémon that are, like, ’tier two’ or ’tier three’ below that, that it makes them unusable.” And so, because the Pokémon are so much closer in power, he explains, “it makes the field much wider, and then it’d be hard to play against everything [in preparation].” Through all of this, Glick is really explaining another hypothesis, another problem in need of working out. Combine the career-shortening risk of flying from tournament to tournament, with the impossible breadth of this year’s playing field, and the result is the kind of scale that seems insurmountable. But to Glick, the solution is clear. “Long story short, experience is really important,” he says. “In order to win the World Championships, you need a lot of experience, and you have to be experienced in a lot of different scenarios that you’re not super familiar with, and you also need to be really familiar with your calculations.” It’s impossible to have an answer to every Pokémon in the game, he reasons, and so the solution is to do the opposite: build a team you’re so familiar with that you become the problem for everyone else. It’s mid-morning on 18th August, less than a day before the 2022 World Championships, Pokémon’s most prestigious tournament, begins its first round - and Wolfe Glick is looking for a pot. We’re talking in person now, sitting outside a solitary Starbucks on the noisy footbridge that takes you to the Excel Arena from Custom House DLR. Glick is confident. Focused. A little excitable, as he talks rapidly but deliberately, through the pre-tournament nerves. He states his belief that he’s prepared to the best of his ability, repeating similar lines back to himself like an athlete reciting a self-affirming mantra. “Right now I think that this is the best place I’ve ever been in with regards to my preparation,” he says. “It’s not the kind of game where you can ever expect a victory in a tournament, or even over another player,” and so his position, he explains, is that “where I’m at is that I feel really good about my team. I feel really good about my preparation”. But before that, details. “We’re making a big stew,” he tells me, explaining his final plans before kick off, “which is gonna carry me through. It’s gonna be good for dinner tonight, to get the right nutrients, but also I intend to eat it every day that I’m in the tournament for lunch, because it seems like it’d be a good option for that. “But,” he concedes, “we don’t have any pots.” Glick’s quest for a cooking pot exemplifies a fastidious approach to preparation that he’s taken up until now. Travelling from his home near Washington D.C., Glick arrived in London a week early, to get accustomed to jetlag. He planned for UK hotels’ frequent lack of air conditioning, off the back of this summer’s heatwave, deliberating over whether or not he should buy a fan. He planned who he would stay with - trusted friends, who were also competitors that could look out for one another. And he planned all his meals for the week. Hours before the tournament now, he speaks in solid bursts of explanation. Between them he’ll pause, pushing his glasses up his nose when he corrects himself or reworks an answer, tilting his head to the side when thinking of the right word like he’s searching for solutions again, reaching for more precision than before. Even then, he’ll regularly find himself on a roll, running through rapid details and fresh discoveries. Occasionally his leg bounces while he talks. He goes on, “I think that compared to every other year - aside from maybe 2016 - the work that I’ve done this year blows every other year out of the water. It’s not close to comparison. And that’s what is within my control. I built a team that I’m happy with. I feel really good about the prep work that I’ve done. And so I’m trying to detach myself a little bit from the result, knowing that the result is out of my control. But the stuff that’s in my control I feel really good about.” It’s an argument you can feel Glick having had with himself over the weeks and months beforehand - what can he prepare for, where does he draw the line? - as though he’s had to learn to live with being unable to control everything, coming to terms with the unpredictability of Pokémon, as much as being truly happy with it. “Of course, it doesn’t mean I’m gonna beat every weird thing,” he says, “it doesn’t mean I’m gonna even do well. But I think that I’ve gotten to a point where I really do feel comfortable.” Where major tournament prep might normally take a couple of weeks for players like Glick, this year he started his Worlds preparation as soon as the US Nationals, the final pre-Worlds competition held in late June, were over. He “got ahead of” his videos, lining them up in advance so he could keep his channel ticking over before the tournament. And then he knuckled down. For over a month he was spending “14 hours a day, every day, with one day rest” on preparation. Preparation has become much easier - I’m reminded of something he mentioned in our first conversation, where he recalled “having to load the game at the exact 100th of a millisecond that I needed to,” in order do encounter a legendary Pokémon a specific frame to get it with the right competitive attributes. These days, things are less time-intensive in terms of sheer grinding, but Glick’s filled every minute of that spare time with strategic and mental preparation for Worlds. In our first chat he described a typical day. “Basically, I wake up, and then I typically do my best thinking in the morning, and so I’ll think of all the problems that I faced the day before, and I will try to come up with solutions. And I’ll theorise about that and do a lot of thinking and writing about where I think things need to go.” After that he’ll play a few games, typically with a friend - Glick’s close with a few other competitive players, which may seem strange but in Pokémon is quite natural, the scene being endearingly collegiate in places. Then he’ll “take a step back, watch the replays back, reflect on that.” Then, something important. “Then I’ll typically take a step away for a while, because something about Pokémon is that there are a lot of diminishing marginal returns with the amount of time that you put in. If you’re practising or working, and you are not in a good headspace for it - like if you were tired, or just mentally drained - you might end up doing more harm than good. Because you might think that something doesn’t work when actually it does work, for example. Or you might think you have a weakness to a team that you actually don’t have a weakness to. Nevertheless, Glick kept this cycle going for months, and finished his prep “the day before” he left to head to London, taking one last day to rest (and squeeze in another three hours of work.) “I gave myself a long runway, basically.” After some reassurance that nothing would be made public before the tournament, Glick agreed to show me a small section of his notes for the World Championships. He is, if anything, eager to share them with someone, pulling them up on his phone and passing it to me with the kind of attempted subtlety of a teenager showing you something illicit in public. On his phone, a folder of separate documents, around a dozen in total, with one for each player he’s identified as a major opponent that he might eventually face. In addition, a whole deck of flash cards. “So,” he says, relishing the detail, “a lot of the work that I did wasn’t actually on the specific team itself, it was on kind of more general stuff. So for example, before I had a team, what I did is I went through and I identified the players who I thought were, like, major threats to win the tournament - and for each of them, I watched probably 10 hours of video and I made an analysis of strengths, weaknesses, general notes.There’s probably some other stuff in here, like common leads,” the Pokémon they most often send in first, “their past teams, stuff like that.” “Basically, going through and breaking down, like every tendency that they have that’s exploitable.” The opposition analysis he estimated at around 60 hours of work. “Then I also memorised this 16-page document of just calx,” he says, flicking through page after page of bullet-pointed calculations, typed up into sentences on exactly how much certain moves will do for and against his Pokémon, and a variety of others (it’s not as simple as a move with 100 damage taking off 100 of your opponent’s HP; types, resistances, natures, the stat builds of your Pokémon and your opponents’ all factor in, on top of any in-game modifying moves that might’ve been used already). A typical example: +3 252 Atk Zacian-Crowned Sacred Sword vs. 12 HP / 4 Def Dynamax Kartana: 248-292 (91.1 - 107.3%) - 43.8% chance to OHKO (one-hit knockout). “This is about half. So it’s probably about 32 pages,” he says. All of this is committed to memory? “I mean, more or less. I make mistakes occasionally, but yeah. I have a very good idea now of how much damage my team is going to do.” We talk a little more before he heads off to finish those last-minute preparations, at which point that sense of necessary stoicism that’s permeated all of his mantras shows itself again. “There’s not a clear way, or right way to prepare,” he says. “Like, I did all this work - it’s the first time I’ve done all this work. We can’t say for sure if this is a good idea. I mean, I really do believe it was a good idea,” he laughs, “but we can’t say for sure. There’s not a template for, ‘Oh, this is how to prepare for Worlds.’” Early in the conversation, he hedges expectations. “There’s a real chance I get knocked out on the first day of the competition. There’s always that chance,” and the same topic comes up again as we wind down. “I have gone to every World Championships trying to win. I have only succeeded one time, but the goal for me has always been to win. But the secondary goal this year is I would love to make it to the second day of competition. The ultimate goal is to win, but I really hope that I can at least get this far as I would love to make day two, as it’s called. Because I think it’d be really difficult to put hundreds of hours of work in and then not be able to play in the main event.” As a few fans start to notice Glick, sitting prominently out the front of the café, we decide to wrap things up. The next day, Wolfe Glick needs to win six of his eight matches to progress. He loses his first and his second, he wins his third and fourth, and then loses his fifth, meaning that, without a bye to day two, Glick is knocked out in the first round. It’s his worst ever finish at the World Championships. A few days later, Wolfe Glick is transformed and yet utterly the same. What’s changed is his mood, the vibration of excitement, as he sat outside the café flying through notes and politely greeting any passing fans, is now gone, replaced with a kind of informed exhaustion. The mood of someone who knows they’ve learned a lesson, but one they’re yet to really comprehend. We’re sitting inside now, the bustle of teenage fans and competitors’ families who’d flown in from around the world replaced with quiet laptop workers and a couple of commuters passing through. What remains the same is Glick’s perspective. His relentlessly searching eye for strategic imperfection. I ask him what happened - none of Glick’s matches were streamed, so few people saw them unfold live. We talked about luck before in Pokémon, I said. The amount of surprises that may come up- “To be honest,” he says, cutting in, but politely, “I don’t really feel like I can blame luck for my performance. I think that my preparation was good, and my team was good, so - I think my headspace, the day of, wasn’t where it needed to be.” This is what Glick is yet to fully comprehend. “I’m not sure if it was pressure, or nerves, or just, something? But when I was playing my games, I felt like I was watching somebody else play. “On a scale from one to 10, with one being the worst Pokémon I’ve ever played, and 10 being the best, five being my average, I never got above one. It was a really kind of weird, almost out-of-body experience, where all of the skills I normally have when I play, I wasn’t able to access. “Normally I can think two to four turns ahead, depending on how complicated the game state is and how much my brain is moving, and I couldn’t even think one turn ahead - like moves that had direct consequences that were negative for me I was still making, because I just couldn’t project. “It was a really weird experience and obviously a really bad time for it to happen, it’s my worst Worlds finish ever, it’s by far my worst tournament finish of the season as well… but, yeah. I don’t really think I can blame luck for this one. My matchups weren’t super easy, but to ask for both good luck and [good] matchups, and good luck in the game itself, those aren’t conditions that you should expect to be getting every tournament.” Dissecting Glick’s performances, even just a day after the tournament was over, you get the sense he’s already worked them over a thousand times. The first two matches, he explains, were both against Japanese players with “very unconventional teams,” neither of which he’d encountered in practice. As ever with competitive Pokémon the explanations are complicated, but briefly, the first was built around an esoteric Torkoal - a typically weak Pokémon rarely if ever used in the current season - plus a combination of the more powerful Kyogre and Gigantamax Venusaur. It made for a strangely niche mix of Pokémon that could change and take advantage of the weather, with the ultra-slow Torkoal countering Glick’s usual solution to the suped-up Venusaur, which is to use a move called Trick Room (allowing slower Pokémon to move first). “I was kind of pinned in both directions.” From here he was on the back foot, freezing up and making uncharacteristic mistakes. “It’s one thing to have a bad matchup but to [still] be familiar with the kind of crucial points in the matchup - but I had to figure all that out round one, and the opponent just had way more tools than me. But even with that, I still had pretty clear opportunities to win that I just missed in the moment. “The second opponent was, again, a team that I never expected… I probably played over a thousand games in practice for that and never saw anything close to the team that I played against, so again that was really close and again I kept making mistakes to lose games that were very winnable.” He won his next two matches easily, before freezing up again and throwing away the make-or-break fifth, despite winning its first round. “I won the first game very convincingly, in the second game I was in a great position but it just dragged on for a really long time. I made a couple mistakes there, lost the second game, and then in the third game, I led Pokémon that were strong in general, but he predicted exactly what I would lead - he ‘counter-led’ me - and then it was really hard to win from there. “So it’s because I was sloppy in the second game, I didn’t close it out when I could have won, and then it went to a third game, they made a really good call early on, and that was it.” It’s here, a day after the tournament’s over, that you realise Glick’s already analysed his results to death. After getting knocked out, he immediately got to work testing, joining a side tournament called the London Open, held exclusively for those knocked out at Worlds: “I was like, okay, was this a team issue and I’m just being stubborn about it, or was it a me issue? And I went eight wins one loss… so the team clearly had what it took to do well.” Then he thought about his wider strategy, his approach to preparation as a whole. Remember how Japan and South Korea have different rules for qualifying than the rest of the world? “This year had a tonne of Japanese players, like far more than any year in the past, and that actually really significantly altered the playing field,” he suggests. “Players in Japan, to qualify for their tournaments, they use a very different system that involves like a WiFi tournament, which is best-of-one, and then a single best-of-one round robin tournament. In the US, tournaments are best of three, so players need more consistency; in Japan, you can get away with far more unorthodox strategies, because you’re only playing one game, so there’s no time for adaptation.” In other words, the field was “especially volatile” as a result. Is that the one big thing to take away then, to make the sacrifice of grinding next time for a bye to day two? “No,” he says. “It’s a small thing to take away - it’s not the main thing. I don’t have a main takeaway yet. “I need to reflect, I need to figure out-” he cuts himself off. This, surely, is the actual takeaway for Glick. The way his mentality shifted, how the games slipped away from him. “This was a very, very, very, very bad performance. Not the result, but in how I literally performed. I could have won. Even my ‘one out of 10’ is capable of winning, is the truth -” He cuts himself off again. “That might not be true. That’s not true. I take that back. But I’m capable of winning games, at least. The result doesn’t always match the performance being below par, basically. So variables apart, that, to me, is the concerning part, so I need to figure out why that happened. And then figure out if I can do anything. “It’s happened a couple times over my career - it used to happen a lot more a couple of years ago, but in recent years I was really working on it, and it hasn’t been a problem all this season. I felt very present, and very, like, aware of my decision-making at all of my tournaments. So I wasn’t anticipating it being a problem for this one, because it hasn’t been a problem in like, a couple years. “It just randomly flared up again,” he says - and then immediately corrects himself once again. “Not randomly. It flared up again, unexpectedly. The issue is that all of my work to counter it is in not letting it happen in the first place, not: knowing, now that it’s happening, snapping back out of it. It’s tough, because it’s not something that’s really easy to simulate in practice - it’s not, you know. But I believe that it has a solution and I just need to figure out what is going on, and then how I can work to prevent it. Or re-centre myself.” During our final conversation Glick flickers between this kind of detached, cold-minded analysis and another, more emotive part of himself, two competing philosophies on what a winner’s mindset really looks like, a driving fire against keeping a cool head. Either way, clearly he is still raw from the surprise of going out so soon. I ask him how he’s personally feeling, putting all strategy aside, and after reflecting on how he’s glad to just be back playing Pokémon after the three-year, pandemic-enforced break, he says, “I’m disappointed.” “I worked really hard for this. And it was my worst Worlds ever, by a pretty large margin.” And yet, each time he gets somewhere close to self-pity, he self-corrects. “It’d be easy to feel like: I put in all this work - hundreds of hours, if not more - and in the end, I couldn’t even access any of the prep that I did. My brain turned off and then I got eliminated. But the truth of the matter is I’ve been doing this for a long time, since 2011, and to me, the crux of Pokémon, the way that I play at least, is improvement. It’s an incredibly difficult game. It’s such a difficult game that I don’t think I’ll ever be able to fully convey it to people who don’t play. So one of the nice things about that is that you can always get better. There’s always another Worlds. “So yeah, I’m really disappointed. And I’m really, really frustrated with myself, I really feel like, if I had played at my average I could have made it through. I think that with my team and my prep, I could have won the tournament if I played at a five out of 10 - I played at a one out of 10. So that was bad. “But it’s not random, right? There’s a reason why I wasn’t able to play well. There’s a reason why. It’s been pretty hectic, I’m still running around, but once I get home, when I have time to settle, I really want to sit down and think about: what do I do well, and what do I do wrong? Where was I lacking? What caused this to happen? So that next time I don’t lose for the same reason. “It’s good data, but it’s a very challenging problem. It’d be one thing if I was like, ‘Oh, I built a bad team’ - then that’s easy enough. But to say, ‘Oh, your brain basically turned off, figure that one out?’ It’s gonna be difficult, but I’ll do my best.” It’s a long way from where Glick was during our first conversation, in the comfort of his recording room, where he talked about his ambitions to bring competitive Pokémon to the masses, and taking a “bigger step” than ever before. Success at Worlds would undoubtedly have helped, and with so much work behind him, and such a shock loss still in his system, he’s tired. But throughout our final conversation, including the many self-corrections and verbal footnotes, Glick’s confidence remains unwavering. He returns to his mantras, the athlete taking over the analyst, only there’s a sense of self-preservation to the words now, the kind of defiant certainty that only comes after you’ve been presented with a chance for shattering self-doubt. I ask him if his sense of responsibility - for growing the VGC community, and his dream of selling it to the masses - makes the disappointment at this tournament even more profound. He pauses. “Maybe it should, but it’s also…” he stops again, finding his words. And then a return to certainty. “Here’s what it is: I might be the greatest Pokémon player of all time. Maybe. This close. I’m up there, at least. And having a bad tournament doesn’t take that away from me. Me bombing at this tournament doesn’t change - it doesn’t take away my accomplishments, and it doesn’t take away my skill level at the end of that tournament. So of course, I win Worlds, I build up all this momentum, I get people super excited for VGC, I parlay it into Scarlet and Violet, it’s great. That sounds nice! Maybe I’ll do it next year. Probably not. That would be great - but the truth of the matter is that I am phenomenal at Pokémon not because I win every tournament, but because of me, who I am fundamentally at this point. So I don’t believe that a single bad result defines anybody long, let alone me. So no - it could only help [winning Worlds] but it’s not gonna hurt. It doesn’t take away my accomplishments. In my opinion.” There’s an irrefutable irony in the air as we talk. Glick’s fixation - his obsession - with creating certainty from uncertainty, of mastering the unmasterable, is as much a part of why he failed this time. In reducing the chances of burnout, preserving his longevity and his legacy, he created more uncertainty for himself in having to face wildcard teams from Japan, unfiltered by the meta that takes hold from day two. In practising so hard, for so long, he might have “overprepared,” as he put it. “Maybe I played too many games, and made it hard to snap out of autopilot.” Above all, though, there’s irony to his choice of game. A mix of “chess meets poker,” as he put it to me in our first conversation. One that he describes as “incredibly complex” - too complex, as he says, to put into words. Of all the games to bring an empiricist’s eye for order too, he chose one built on a near-infinite chaos. A week later, after he’s returned home and taken some time to rest, Glick takes to Twitter. Between posts about new Scarlet and Violet announcements, self-deprecating jokes, serious chats about the cost of competing, brand partnerships, and VGC memes about Bidoof, one tweet stands out: “I am going to win the 2024 Pokémon World Championships.” Pokémon, of all games, is the one where certainty is impossible to find. Wolfe Glick remains determined to find it.