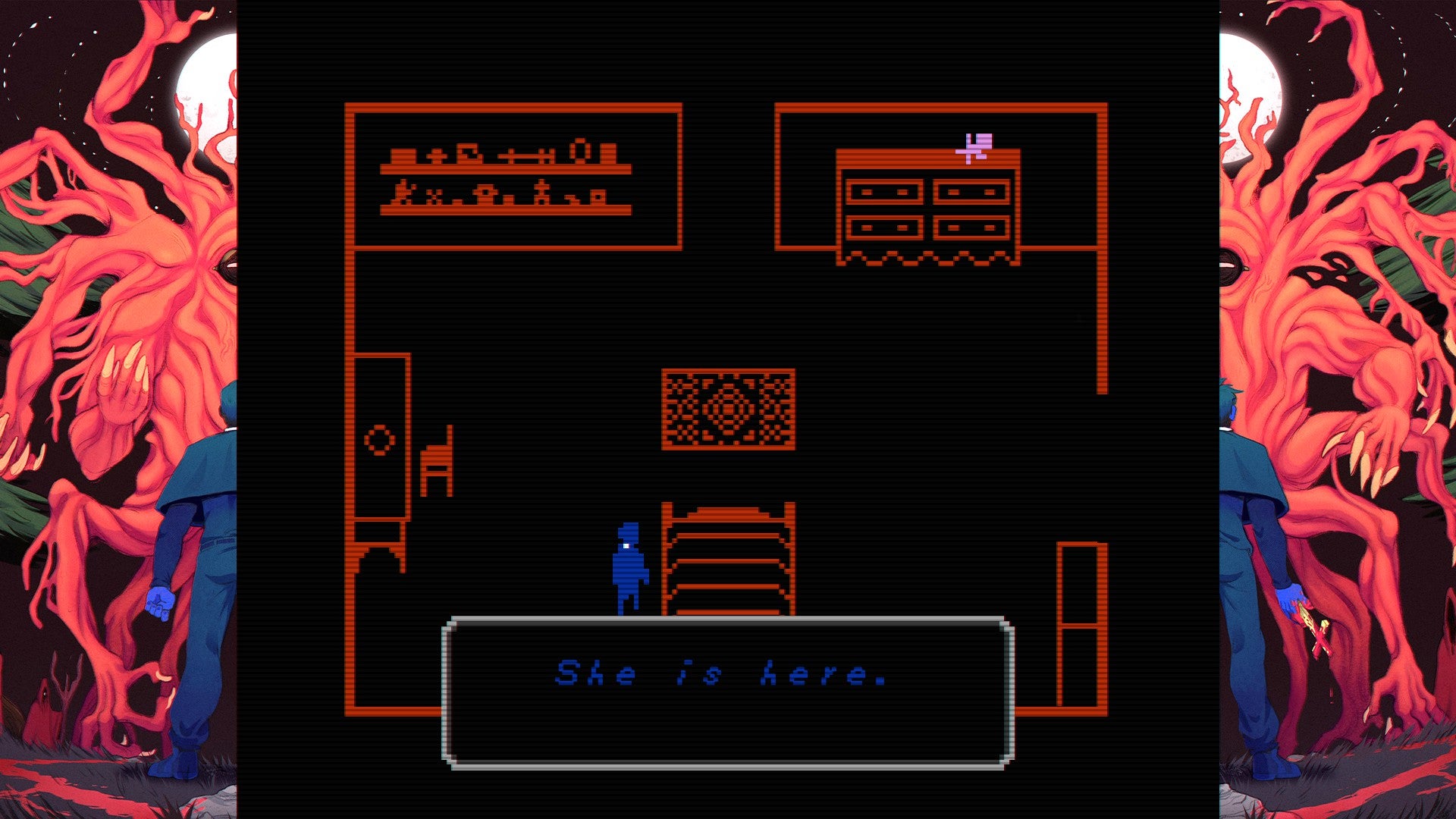

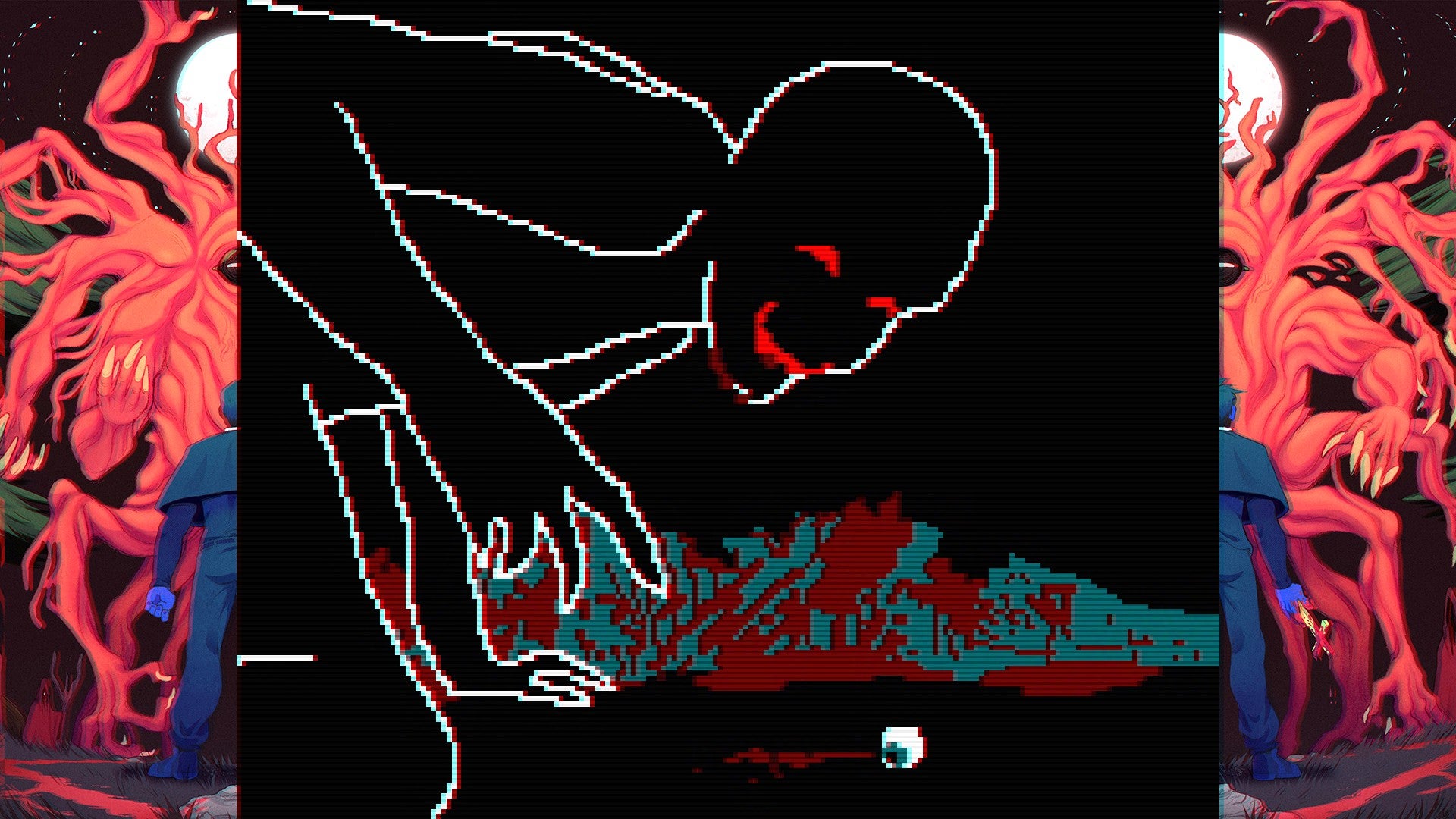

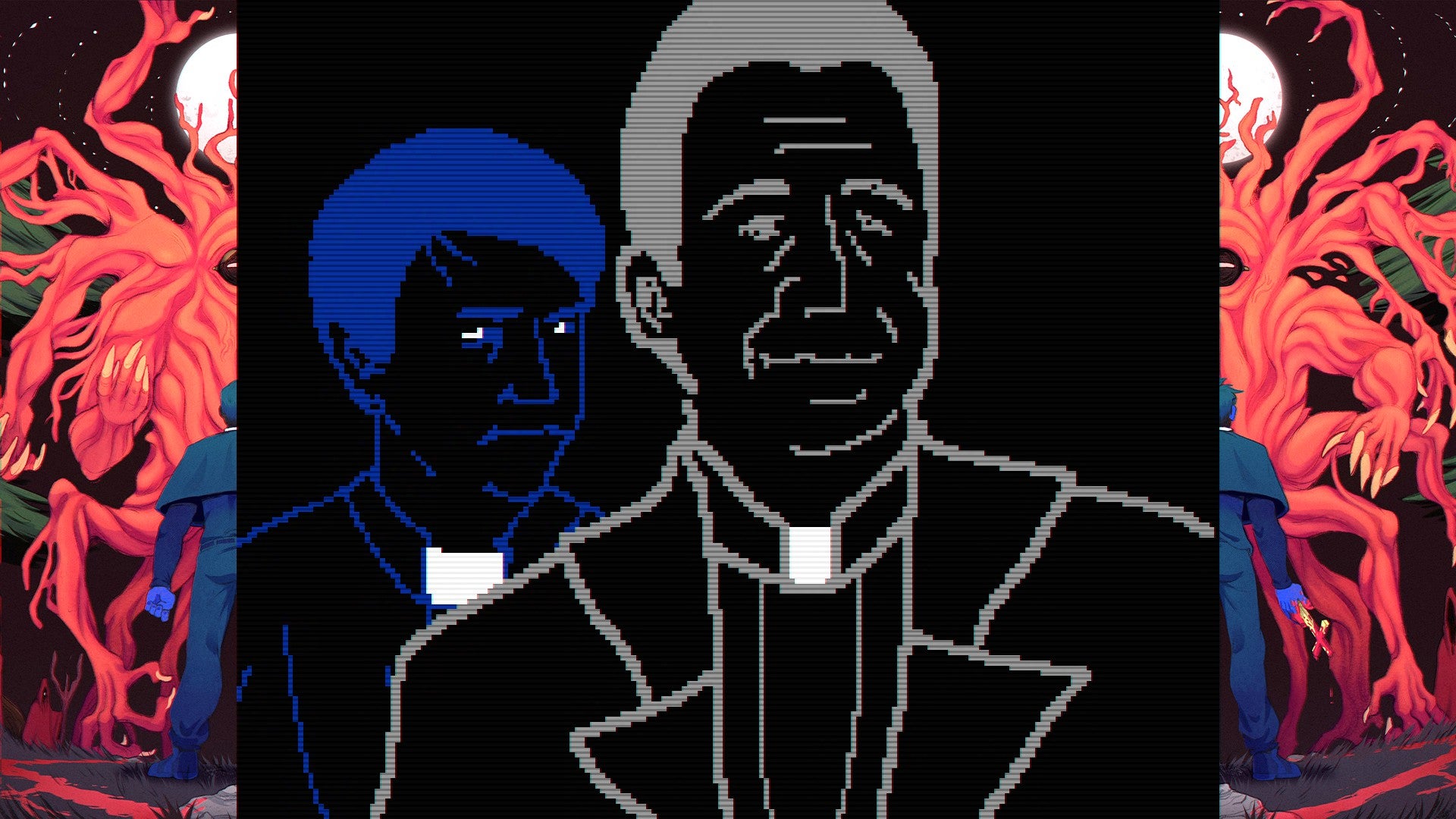

The theme is exorcism, and Faith begins with you, a priest, driving along a road and parking by a forest, then getting out and walking into the trees. You’re going to finish what you started, with or without the Vatican’s permission, you’re told, and that’s really all you know. Faith is a game that doesn’t tell you much because working out what you’re doing is part of it. Mechanically, though, you can’t do much: you can walk around and hold up a cross. And holding up the cross near certain objects seems to exorcise souls from them, and doing so produces a note. And notes are important. They are what fill in the story around you, detailing who you are, what you’re doing, what you’re looking for and why. And they’ll give you clues about what you’ll find when you get there, too, the answer to that one nearly always being “demons”. So, you walk. You trudge through a forest one screen after another as you try to work out where to go. And every so often, you hold up your cross to reveal another note. And the immediate feeling is this all feels very slow, almost soporific, with the garbled classical music - the sort you’d listen to while relaxing in the bath - in your ear. But then, screech! A four-legged horror that looks like a deranged piece of spaghetti darts out from a corner of the screen and tries to get at you. It moves much more quickly than you and crashes in with a discordant scraping sound, making you panic, but instinctively you hold up your cross and it is gone. The effect is complete: now, you’re on edge. Now you know the game has teeth. This is Faith in a nutshell: stillness and nothing, then screech! and something coming at you, and quick. And it’s effective - more effective because there’s nothing else going on. Why didn’t more games do this in the 80s (did they? I might have been too young to know)? I suspect the answer is partly because they couldn’t. Faith, you see, is sneaky. Every so often it will mix in other surprises you don’t expect, things like much more richly animated 3D sequences, albeit done with simple line drawings, that show some of the horrors you’re running from up close, or some of the main characters. And they shake the player around a bit more. There’s a wonderful moment where you see the stereotypical image of a longhaired girl from a Japanese horror film emerge in front of you, then the game announces “She’s here” and a chase begins. One presentation works really well to reinforce the other. Whether any of this is technically 8-bit, I don’t know. But I expect what’s more important is the feeling of it being a game from your childhood so it can play around with your expectations from there. You don’t expect a game to be able to do this, but it can. This feeling of the game being capable of more than you thought builds as you progress through its three chapters, each of which are a couple of hours long, depending on how long you’re held up by certain puzzles, or note searching, or enemy encounters, which can be very annoying - there’s a lot of dying and trying again as you try to figure them out. That plus some tiresome traipsing around are my main drawbacks in the game. But save points are usually close so you don’t have to redo much progress. Soon, you’ll realise it’s all connected, the story and characters. They even overlap as you go back in time and witness the beginning of events you’ve already seen pass. And then you’ll finish a chapter and the game will announce that you’ve seen ending one of five and you’ll go, “Oh, that’s smart,” and consider playing it through again, because maybe you didn’t have to kill the girl, and what will happen if you don’t? That’s Faith: smarter than it looks, deeper than it looks, scarier than it looks. It’s a game that deliberately uses a little to achieve a lot, and disarms you.