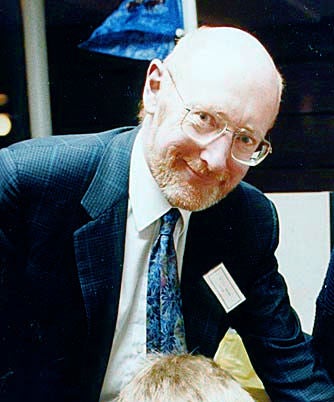

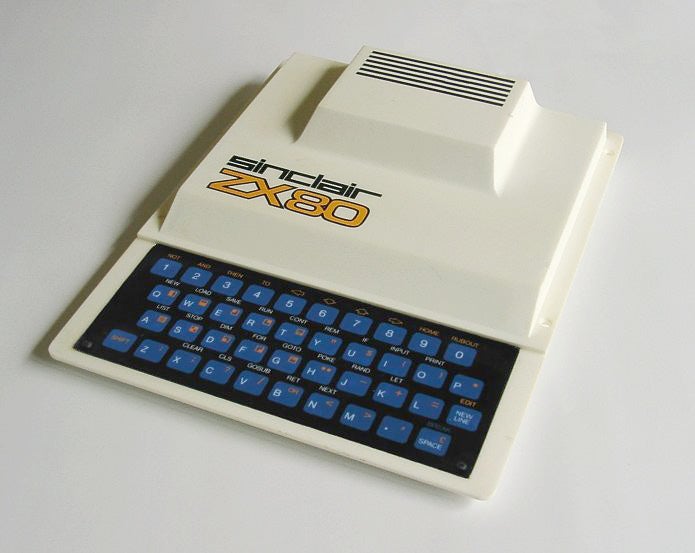

Sinclair was an inventor first, a businessman second. Born in 1940, he was a precociously gifted child, particularly good at mathematics, and both his father and grandfather were accomplished engineers. A voracious reader and tinkerer, he spent his school holidays teaching himself the things that his secondary school could not, and by the age of 14 had reportedly already come up with a design for a submarine. History, sadly, does not recall if he ever attempted to build and sail it. Fascinated by the new technology of electronics, the young Sinclair took holiday jobs at relevant companies and tried to pitch his managers with ideas for electric vehicles - an obsession that would run throughout his career, and one of many examples of how far ahead of his time he was. Before he had even finished his A Levels - physics, pure maths, and applied maths - he was selling DIY miniature radio kits by mail order, working out his material costs and profit margins in an old school exercise book. This grew into an actual business, selling calculators and other gadgets, as well as producing early kit computers for schools and colleges. It’s here that Sinclair’s story branches off into our world of gaming. Envisioning a future where every household would have its own computer, Sinclair began putting together what would become the ZX80, which had a whopping 1k of memory in its basic form. Sinclair’s stroke of genius was producing a computer that was affordable by most ordinary consumers. At a time when computers cost at least £700 (over £3000 adjusted for inflation), the ZX80 retailed for less than £100. You could even save more money by buying it in kit form, like the radio sets Sinclair had sold as a teenager and putting it together yourself. Launched in 1980, as reflected in its name, the ZX80 was an immediate hit, and was quickly followed by the ZX81, hurried into production to catch the eye of the BBC, which was embarking on its own quest to supply computers to schools. The Beeb chose Sinclair’s rival, Acorn, but the competition lit a fire under Sinclair who pressed ahead with his greatest creation, the ZX Spectrum. Available in 16k and 48k versions, the Spectrum improved radically on the ZX81 by offering a limited colour palette, rudimentary buzzer sounds and the ability to create bespoke graphics. There had been games for the ZX81, of course, but with the new dizzying possibilities of the Spectrum, what had been a niche market quickly exploded into a cottage industry as amateur developers rushed to produce interactive entertainments for the small army of kids who had been gifted a Spectrum on the understanding that it would “help with your homework”. It’s important to remember just what a seismic shock this new frontier was. Sinclair never intended for his computers to be games machines, but that was what the market decided they were. Within the space of a few years, the idea of having a computer in the home had gone from a fantasy for all but the wealthiest businessmen to a reality, even for council estate kids. The number of office software packages dwindled; the number of arcade games rocketed. The prevalence of the “bedroom coder” is somewhat overplayed, but it’s no surprise that as news of Sinclair’s death broke, social media was filled with tributes from hundreds of veteran games creators saying how their first experience of coding came on a ZX81 or Spectrum. Between 1980 and 1982 “making games” became a valid way for anyone to make a living. If there’s one triumph that Sinclair deserves to be remembered for, it’s that early democratisation of access to computer technology. That would be enough to earn Sinclair a place in the hall of fame, but there was something unique about the Spectrum in particular that made it endure where other computers of the era didn’t. The very fact that Sinclair himself became a totemic figure, lovingly referenced in games magazines of the era as “Uncle Clive” speaks volumes. Despite reportedly being rather taciturn and serious in real life, the popular image of him as a lovable egghead leader to a generation of kids grew and spread. By contrast, few even knew who created the Commodore 64, the Spectrum’s great rival. A big part of this personal connection that owners had with their Sinclair hardware stems from Sinclair’s tinkering nature. Looking at the ZX Spectrum today, it’s a truly bizarre thing. In technical terms it was an underdog, and underdogs inspire defensiveness. Underpowered in comparison to its competition, its colour graphics clashed garishly if they overlapped, its sound buzzer squawked and farted, and - most famously of all - its keyboard was made of rubber. It’s those squishy keys that stick in my mind as the evidence of Sinclair’s offbeat genius. A cost-saving measure to avoid the expense of moulding dozens of individual keys, the rubber mat that sat underneath and poked through the Spectrum’s metal case was a smart solution to an engineering problem, but a baffling limitation in practical terms. That it came slathered in multiple functions and BASIC shortcuts accessible through various shift keys was also important. This was a computer that showed its work, that rubbed your face in the arcane language that made stuff happen. Just to look at the Speccy keyboard was a challenge to try writing something of your own. The Spectrum was nothing if not an illustration of the old maxim that necessity is the mother of invention and it sold by the bucketload - over 10 million by the end of its lifespan. Britain’s nascent game developers couldn’t afford to ignore it. At the same time, getting its claustrophobic architecture to produce better, faster, more eye-catching games required inventive coding and design skills. Any programmer who was around in that era can attest to the often-ingenious tricks used to make Spectrum games even move around on screen. And that, in a roundabout way, is what made Sinclair a world-changer. The games industry would still have existed without the Spectrum, of course, but it would have been dominated by US companies like Commodore. UK developers would still have sprung up to service the new market of eager young gamers, but they wouldn’t have had to navigate the quirky eccentricities of Sinclair’s creation. A key spark of necessary invention would never have fired. The UK has always punched above its weight in games design, and that’s because of Sinclair. Trace back the family tree of pretty much any UK games companies today, and you’ll find connections to 1980s startups that benefited from the leftfield problem-solving Sinclair’s computers demanded. It’s not just that the Spectrum created a commercial market that allowed a generation of UK coders to spring forth, it demanded inventive thinking that helped to give British games design a unique mix of personality and invention. Pick any of the pantheon of great UK games, the blockbuster franchises that are still going today, and there’s Spectrum DNA in there. Despite the success of the Spectrum, Sinclair didn’t stay in the computer business much longer. After launching a pocket-sized television, he turned his attention to a new company and developed the electric vehicle he had been dreaming of since childhood. The Sinclair C5, sadly, was a humiliating failure. An electric tricycle, it was mocked for its toy-like design and its lack of safety - the rider sat so low to the ground that they were below the eyeline of most car wing mirrors, and with no canopy to cope with British weather, the prospect of being surrounded by looming traffic in a downpour did not appeal. The C5 project was launched and gone in under a year, and Sinclair sold his computer business to Alan Sugar’s Amstrad to keep the lights on. Throughout the 1990s and into the early 2000s, Sinclair continued to pursue his goal of doing for electric transport what he had done for home computers. None of his follow-up plans came to fruition, and before long the Sinclair company was reduced to a handful of full-time staff, and eventually just Sir Clive. There’s little doubt now that Sinclair saw the future, even if he was never quite able to turn all of his visions into commercial reality. We watch television on devices that fit in our pocket. Electric vehicles are now the norm. Crucially, for Eurogamer readers, almost every home has at least one computer and the UK still has a world-class reputation for creating imaginative, fascinating games to play on them. It’s an incredible legacy.